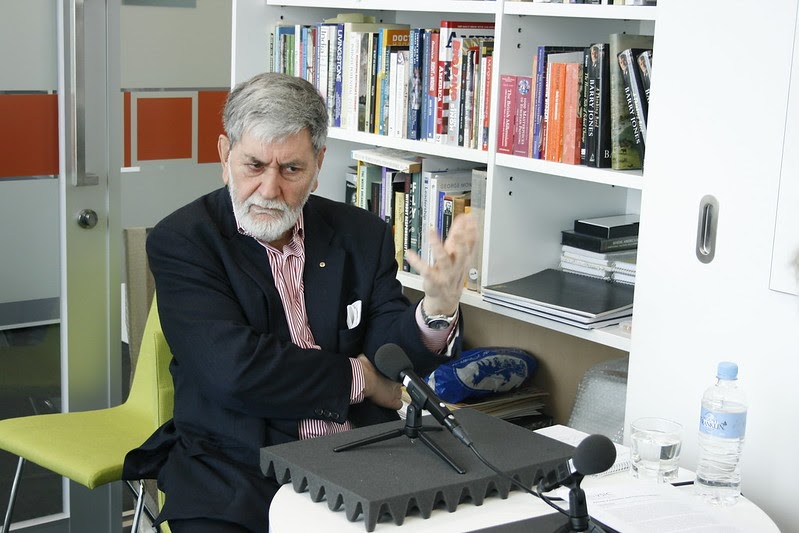

In the greatly privileged role of an interviewer for the National Library of

Australia’s Old Parliament House political and parliamentary oral history project, I recorded a long interview with Barry Jones, the Australian polymath, politician, science buff, quiz-king, author, collector, public intellectual and much else besides. I have to admit to being scarified by Jones, more by the sense of his vast capacity and knowledge, than any wilful attempt on his part to be intimidating.

In the interview, Jones tells a story he has often repeated about an encounter with John Howard in 1996 and soon to be Australia’s 25th Prime Minister. I might leave it for Barry to make his own way here, and simply quote him in relevant part:

Barry Jones: I ran into Howard somewhere and I said to, I said to Howard, ‘Have you ever read Tolstoy’s War and Peace?’ And he… no, he hadn’t. And I said, ‘Look, if I get you a copy, if I send you a copy,’ I said, ‘would you undertake to read it?’ And he looked at me very uneasily and said, ‘Why would you give me a copy of War and Peace?’ And I said, ‘Well, I happen to think that on the law of probabilities that you will become Prime Minister,

and I happen to think that if you’ve read War and Peace you’d better… be a better prime minister.’ And so he said, ‘Oh.’ Sort of raised himself up a bit, he said, ‘Oh, well,’ he said, ‘on that basis, yes, I would read it.’

So I sent him a copy. And he told me later several times that he had read it, and I’d like to think that’s true. And I often used to reflect, you know, that I, I felt a sense of relief that he had read it. Because I thought if he hadn’t read

it, God, where would we have been in the Middle East? It could have been even worse. But anyway…

capturing of the layered complexity

of battle has parallel insights to

offer on the multifaceted nature of

economic ideas.

Of course, if it was good enough for John Howard to be sent away to read War and Peace to prep him for the nation’s top job, it was certainly good enough for me who, though given plenty of opportunity, had also never read Tolstoy’s towering tome. It might make me a better interviewer, particularly one swatting to interview the encyclopedic Jones.

I applied myself to a cover-to-cover read. But what I found myself dwelling on most of all were those passages where Tolstoy addresses himself to causes and emerges with such a dizzying tie of complexity impossible to unravel. For the causes and complexity of war or, rather, particular battles, I was continuously thinking ideas, more specifically, economic ideas because in parallel with the time I was interviewing Jones, I was also thinking of another project I was working on at the time about the influence of economic ideas. Tolstoy’s writing seemed particularly germane.

It is difficult to know where to start with Tolstoy, there are so many passages of acute insight into causation and human motivation. It is also difficult to know where to stop, as even in translation there is a dazzling quality to the writing and observation that the desire is to simply quote and quote, at length and often. Perhaps the thing to do is to quote and pare, quote and pare and gradually build shape into the relevance of Tolstoy to economic ideas and their spread and influence.

The starting point maybe the first passage that really captured my attention, and it is more a metaphor on the mechanism for how things happen than why, comparing the mechanism of a military machine to large tower clock, each bit interconnected but at the same time blind to the operation of the other parts. Here goes:

The concentrated activity which had begun at the Emperor’s headquarters in the morning and had started the whole movement that followed was like the first movement of the main wheel of a large tower clock. One wheel slowly moved, another was set in motion, and a third, and wheels began to revolve faster and faster, levers and cogwheels to work, chimes to play, figures to pop out, and the hands to advance with regular motion as a result of all that activity.

Just as in the mechanism of a clock, so in the mechanism of the military machine, an impulse once given leads to the final result; and just as indifferently quiescent till the moment when motion is transmitted to them are the parts of the mechanism which the impulse has not yet reached. Wheels creak on their axles as the cogs engage one another and the revolving pulleys whirr with the rapidity of their movement, but a neighbouring wheel is as quiet and motionless as though it were prepared to remain so for a hundred years; but the moment comes when the lever catches it and obeying the impulse that wheel begins to creak and joins in the common motion the result and aim of which are beyond its ken.

Just as in a clock, the result of the complicated motion of innumerable wheels and pulleys is merely a slow and regular movement of the hands which show the time, so the result of all the complicated human activities of 160,000 Russians and French—all their passions, desires, remorse, humiliations, sufferings, outbursts of pride, fear, and enthusiasm—was only the loss of the battle of Austerlitz, the so-called battle of the three Emperors—that is to say, a slow movement of the hand on the dial of human history. (Oxford University Press 2010, Translated with Notes by Louise and Aylmer Maude; Revised and Edited with an Introduction by Amy Mandelker, Book One – Part Three at page 274)

What a marvellous visualisation of, for my purposes, the bi-fold movement of an idea taking hold and its translation to policy and from policy to action. In each case, the ticking clock provides a way of describing a process and lends understanding to some of the stepping and intricate interlocking involved. Even so, as so many of Tolstoy’s further writings make clear, the mechanical, whirring, clunking nature of the clock winding itself out greatly oversimplifies what is really going on in the mind of the cogs that grind the mechanism.

In similar vein Tolstroy moves from the clock to the horse to describe the actions of one of his characters, Weyrother:

He was like a horse running downhill harnessed to a heavy cart. Whether he was pulling it or being pushed by it he did not know, but rushed along at headlong speed with no time to consider what this movement might lead to. (p. 277)

But from the mechanical clock to the touching likening of a man to a horse tied to a cart, Tolstoy moves to the most profound meditations on human causation, as in when he reflects on the 12 of June 1812 when the forces of Western Europe crossed the Russian frontier and war began, “that is, an event took place opposed to human reason and to human nature.” (p.647)

Millions of men perpetrated against one another such innumerable crimes, frauds, treacheries, thefts, forgeries, issues of false money, burglaries, incendiarisms, and murders as in whole centuries are not recorded in the annals of all the law courts of the world, but which those who committed them did not at the time regard as being crimes. What produced this extraordinary occurrence? What were its causes? (p.647)

The superficial causes are quickly set aside – the wrongs inflicted on the Duke of Oldenberg, Napoleon’s ambition, Alexander’s firmness, the mistakes of diplomatists etc. These are but the naive assurances of historians and the understandable viewpoints of contemporaries.

But these and countless other causes urged, depending on the endless diversity of points of view, seem insufficient to posterity. This is where Tolstoy moves on to infinite regress and layer upon layer of complexity.

The deeper we delve in search of these causes the more of them we find; and each separate cause or whole series of causes appears to us equally valid in itself and equally false by its insignificance compared to the magnitude of the events, and by its impotence—apart from the cooperation of all the other coincident causes—to occasion the event…. (p. 648)

Had Napoleon not taken offense at the demand that he should withdraw beyond the Vistula, and not ordered his troops to advance, there would have been no war; but had all his sergeants objected to serving a second term then also there could have been no war. Nor could there have been a war had there been no English intrigues and no Duke of Oldenburg, and had Alexander not felt insulted, and had there not been an autocratic government in Russia, or a Revolution in France and a subsequent dictatorship and Empire, or all the things that produced the French Revolution, and so on. Without each of these causes nothing could have happened. So all these causes—myriads of causes—coincided to bring it about. And so there was no one cause for that occurrence, but it had to occur because it had to. Millions of men, renouncing their human feelings and reason, had to go from west to east to slay their fellows, just as some centuries previously hordes of men had come from the east to the west, slaying their fellows. (pp.648-9)

Ultimately Tolstoy relies on a grander plan, a holy veil beyond which no-one can look. To him, ‘We are forced to fall back on fatalism as an explanation of irrational events ( that is to say , events the reasonableness of which we do not understand).” (p.649)

Along the way, however, his meditations on causes inch us closer to understanding the ineffable, even where that way is piteously blocked to us and shown up as folly. Tolstoy’s dissections help us nonetheless.

Are we reading here, in the next passage I quote, of the causes of war, or of the free-market’s invisible hand, or of human endeavour generally, frantic purposive action under the cloak of deception leading to where, we do not really know. But as we read, flashes of light and insight lead the way even where the end result is opaque, it is opaque but less opaque if that is possible. And before I quote, for some reason I am reminded of Eliot’s line in Four Quartets that tells us that we are only undeceived of that which deceiving can no longer harm. But I digress, or do I:

Each man lives for himself, using his freedom to attain his personal aims, and feels with his whole being that he can now do or abstain from doing this or that action; but as soon as he has done it, that action performed at a certain moment in time becomes irrevocable and belongs to history, in which it has not a free but a predestined significance. There are two sides to the life of every man, his individual life, which is the more free the more abstract its interests, and his elemental hive life in which he inevitably obeys laws laid down for him. Man lives consciously for himself, but is an unconscious instrument in the attainment of the historic, universal, aims of humanity. A deed done is irrevocable, and its result coinciding in time with the actions of millions of other men assumes an historic significance. The higher a man stands on the social ladder, the more people he is connected with and the more power he has over others, the more evident is the predestination and inevitability of his every action. “The king’s heart is in the hands of the Lord.”

A king is history’s slave.

It is so tempting to just go on quoting and, indeed, I cannot resist the following further slab. We started with Tolstoy’s town clock, moved on to the horse tethered to an overloaded wagon, perhaps it is fitting to conclude with something of a combination of the children’s story about who sank the boat and Newton’s apple. But, really, Tolstoy’s fruit needs no outside assistance, it is full of its own dazzle:

When an apple has ripened and falls, why does it fall? Because of its attraction to the earth, because its stalk withers, because it is dried by

the sun, because it grows heavier, because the wind shakes it, or because the boy standing below wants to eat it?

Nothing is the cause. All this is only the coincidence of conditions in which all vital organic and elemental events occur. And the botanist who finds that the apple falls because the cellular tissue decays and so forth is equally right with the child who stands under the tree and says the apple fell because he wanted to eat it and prayed for it. Equally right or wrong is he who says that Napoleon went to Moscow because he wanted to, and perished because Alexander desired his destruction, and he who says that an undermined hill weighing a million tons fell because the last navvy struck it for the last time with his mattock. In historic events the so-called great men are labels giving names to events, and like labels they have but the smallest connection with the event itself. Every act of theirs, which appears to them an act of their own will, is in an historical sense involuntary and is related to the whole course of

history and predestined from eternity. (p.650)

I doubt that Barry Jones would agree with the notion of actions being predestined from eternity or else why would he have pressed War and Peace on John Howard in the first place.

His purpose was obviously, to edify and uplift but by what means exactly

did he imagine that a reading of Tolstoy would make Howard into a better

Prime Minister? It is best to consult Jones directly here (although with minor editing) on what he wanted Howard to derive from the book:

The sense that we make decisions all the time that have cumulative effects over a long period. One of the tragedies about the present political situation in Australia I think is that we’re thinking constantly of immediate self-interest, immediate benefit, thinking in terms of, ‘What’s going to happen to me in the next six months?’ Rather than saying, ‘Well, what, what are the implications going to be in a decade?’ or something like that.

Garry Sturgess: And continuing on the War and Peace theme, one of

the aspects of it is a profound meditation on causes.

Barry Jones: Oh, yes, absolutely, yes. Well, yes, what can one say? Yes, but the point about the complexity of society, the interrelationship between belief(s stemming from the different personality types. I mean, the profound analysis of the difference between Prince Andrei and his view of the world and the more speculative viewpoint of Pierre Bezukhov.

Jones puts himself in the Bezukhov camp and, I have to admit, being disappointed at not having pursued Jones further on the subject but the interview at that point, while still relevant to causation dived into Thomas Kuhn’s work on paradigm shifts and how it is that we move from one way of viewing the world to another?

Barry Jones: Look, very often the, the, the conversion experience has really come out as a result of a, a crisis of some sort.

He references the profound impact of of World War II on Australia’s pursuit of a large-scale migration program. The personalities of leaders he cites as

another factor. The change from Sir Robert Menzies to Harold Holt, for example, freed up indigenous policy. But perhaps my limp pursuit of Jones on War and Peace was partly compensated by discussion about another work with a profound impact on him but also intricately related to the complexity of causation and the nuanced nature of personality, memory and decision-making.

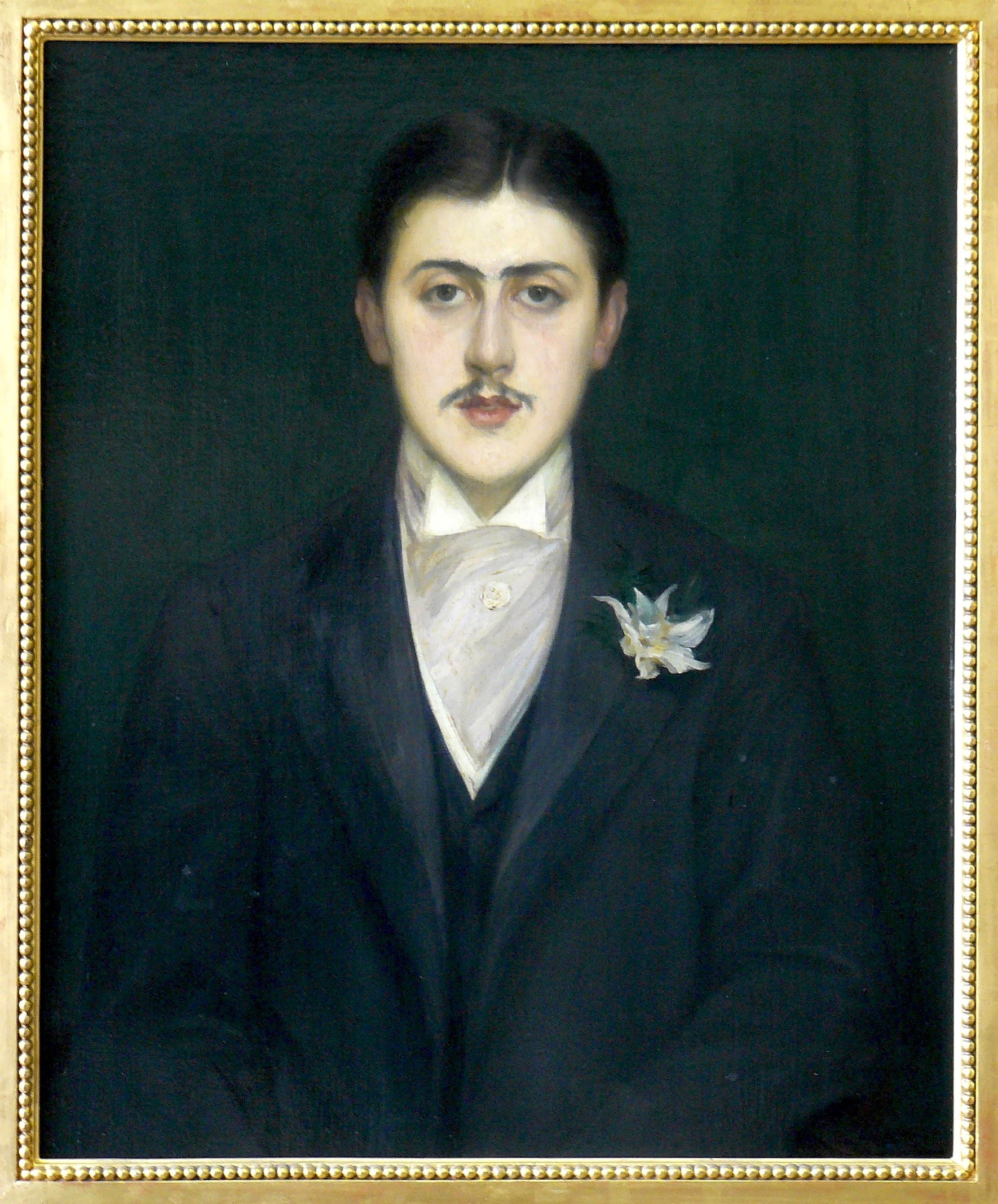

Garry Sturgess: And another book that you mentioned as having profoundly influenced you is Proust’s Remembrance of Times Past or

whatever the translation is.

Barry Jones: In Search of Lost Time is a better description, it’s actually a literal translation. The other, is a Shakespearean quotation. But I think that the common view now is that it’s, it’s really [à la recherche,] In Search of Lost Time.

Marcel Proust, 1892 © by clairity

Garry Sturgess: And what is it that you derive from that book? And is that another book that you would give to a leader or a politician as a

life changing process?

Barry Jones: Oh, I’m just trying to get the idea of giving it to Tony Abbott to read. I don’t think so somehow. I think the extraordinary thing that Proust said, or rather the narrator, I should say, says about In Search of Lost Time is that the book is essentially an optical instrument, and it’s an optical instrument for looking inside yourself. And it’s a matter of really trying to understand how it is that you make decisions, how you relate to other people, what you say, what you don’t say, what you say, what you hold back, the internal reservations that you have, the sheer complexity of day-to-day experience. And, and also those factors sometimes which, which if you measure them objectively, don’t seem to be very important. I mean, the two classic illustrations of the dipping of the Madeleine in, in tea. And the other is the feeling of Combray, I think the feeling of the unevenness of cobblestones as you’re walking. Now, they don’t sound like very exciting issues, but in fact it may be that it triggers off a memory, say, a childhood memory, that’s so powerful that you can’t get away from it, that you’re haunted with it all day. What’s triggered it off? Well, somebody dipping a Madeleine in tea, that’s right. So it’s not very important, no, but the impact that it has on the individual is important.

Garry Sturgess: And that’s interesting because in politics, and it seems to be a skill that you’ve got and a number of senior politicians have got, is the, the idea of stopping that reflection that comes from walking on cobblestones or the tea metaphor that you used to get on with the next thing, the thing that is immediately in front of you, to compartmentalise.

Barry Jones: Well, I mean, you see, it might be that you’ve got a situation where you’re dipping your Madeleine, you’re dipping your little cake in tea and you then go out and you see something horrific. You see somebody fall from a building. And then you think, ‘Oh, look, perhaps it was suicide, perhaps it was just an accident, perhaps it was a failure in the building.’ And, and it’s as if you say, ‘Oh, well, look, I’m just going to walk down the street and not think about it.’ You will in fact… or one hopes anyway… that it will have a profound impact. You say, ‘I’ve got to find out about this.’ And it may be that every time you see the Madeleine dipped in tea it reminds you of some traumatic moment.

An example of the biscuit dipping moment is that when Jones mentioned the sight of someone falling from a building, my mind immediately went to

Auden’s poem and the expensive delicate ship in Breughel’s Icarus that must have seen something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky. The searing events of September 11 swirl in the imagination somewhere too, particularly, say, if you are John Howard and happen to be in Washington when news of the twin-tower disaster is relayed to you.

The eyewitness experience of an Australian Prime Minister of 911 is not to be compared exactly to the unconscious reaching of a childhood recollection nevertheless weighing upon present-time experience. Nor, on its face, was September 11 an economic event. But Howard’s presence on that fatal day, though in Washington, not in New York, is nonetheless a telling reminder that large decisions are, in final result, taken by a collective of individuals, sometimes the one individual, all of whom bring to the moment of decision, emotional, psychic and intellectual histories and all of whom can at the critical time be in the thrall of a biscuit-dipped-in-tea reflection. When I interviewed Howard for the SBS television series Liberal Rule he described his experience in Washington in some detail.

John Howard: Yeah, I’ll never forget it. Um I had seen the president only the day before for the very first time. I spoke to him on the phone twice but I’d never met him face to face until the 10th September, 2001. We had a ceremony at the naval dockyard in Washington to mark the 50th anniversary of ANZUS. Uh I then when to the White House, had a lengthy talk with him and then had lunch and that afternoon, I went to the pentagon ah and met the defence secretary and that evening I had eh dinner with Rupert Murdoch ah and we talked about Australian politics and American politics. The next morning I went for a walk and on the way back I took a telephone call from the treasurer who was in China and we talked about Ansett, which was then in a lot of financial difficulty. I then got back to my hotel room and I was getting changed for a news conference and eh Tony O’Leary eh my press secretary knocked on the door and he said a a plane has hit the one of thetowers of the trade centre.

At that stage, it was the first one. We thought well you know that’s a bad

accident but didn’t quite and then a few minutes later he came around.

He said another plane has hit the trade centre and we knew instinctively

that ah this was eh something quite terrible. I then went to the news

conference and said something very briefly about these events, as I didn’t

know a lot about them and it was while I was at the news conference that the plane hit the Pentagon and I remember after the news conference I pulled the curtains aside and you could see the smoke coming up from ah the Pentagon and then we of course turned on our television set and the whole thing was just unfolding like it was to everybody else around the world and then a short while later the um the head of my eh secret service detail came eh to me eh along with the head of my own AFP detail and said eh you’re out of here. We’re going to take you to the eh basement area of the Australian embassy in eh Washington.

And eh earlier my wife and elder son had gone out and they were picked

gathered up and facilitated through Washington and we ended up in this

bunker eh this basement area and I stayed there for some hours and we were joined by the eh American ambassador, the newly appointed American ambassador to Australia, Tom Schieffer, and I sort of instinctively embraced him and said, Tom, this is terrible. Ah I want you to know how deeply the Australian people feel about this and eh I then did a news conference and that evening I eh went to stayed at the eh the home of the eh Australian ambassador, Michael Thawley. The next morning, I’d been scheduled to give an address to a joint sitting of congress and that of course was cancelled but I wanted to go to congress to express on behalf of Australia by my presence our sympathy for the Americans and I was the only person in the public gallery and they acknowledged my presence and they were very touched that I was there and then they of course debated the issue and passed a resolution.

And that ah afternoon I um or midday I went to a memorial service at the national cathedral in Washington and eh spoke to a number of people including Richard Armitage the deputy to um secretary of state and eh Alan Greenspan, the eh chairman of the Fed who was I was to have seen the following day, I spoke to him and then the eh the United States government arranged eh for me to fly out of eh Andrew’s air force base in Washington on air force 2 and it flew direct to eh Hawaii and it picked up a Qantas flight in Hawaii. It was in fact the first aircraft to leave American air space after the attack. It was a very dramatic occasion and it had a lasting impact on me and you have to have been there to understand the sense of of shock and outrage and disbelief ah that the American people felt. This is, was, an open, blatant,

unprovoked, unjustified attack on their homeland and they’ve never forgotten it and it it had a huge impact on them.